Naalagiursaniq Tunnganarnirlu (Learning to Listen and be Welcoming): Engaging Inuit Perspectives on Timimut Ikajuqsivik (Rehabilitation Services) for Children in the Qikiqtani Region of Nunavut

Doctoral research led by Janna MacLachlan, University of Toronto

Co-researchers: Stephanie Nixon, Andrea Andersen, Anita Benoit, Earl Nowgesic and Leetia Janes

Detailed research summary for service providers

Janna is an occupational therapist who has worked in Nunavut off and on since 2006. Her objectives in the research project were to:

-

illuminate knowledge on how the timimut ikajuqsivik interests of Inuit children in the Qikiqtani Region of Nunavut can be understood and supported by foregrounding perspectives of Inuit and Inuit worldviews.

-

compare and contrast requirements for supporting the timimut ikajuqsivik interests of Inuit children with current mainstream rehabilitation service norms.

The rationale for these objectives was based on a recognition that:

-

There have been calls for Inuit knowledge to be represented in services but little done to consider how this can occur.

-

Mainstream rehabilitation is dominated by Eurocentric norms, which may be inappropriate and even harmful when applied where they are not a good fit.

-

In places where service access is limited, it becomes especially important to reflect on the composition of services offered.

-

Relationships are central to service evolution in Nunavut.

The research involved meeting with 25 participants in two communities in the Qikiqtani Region. Development of the findings was supported by participatory analysis and discussion with collaborators and stakeholders. This handout contains tools that emerged from the findings that may be helpful to service providers.

For more information, visit http://timimutikajuqsivikresearch.ca or contact: janna.maclachlan@alum.utoronto.ca

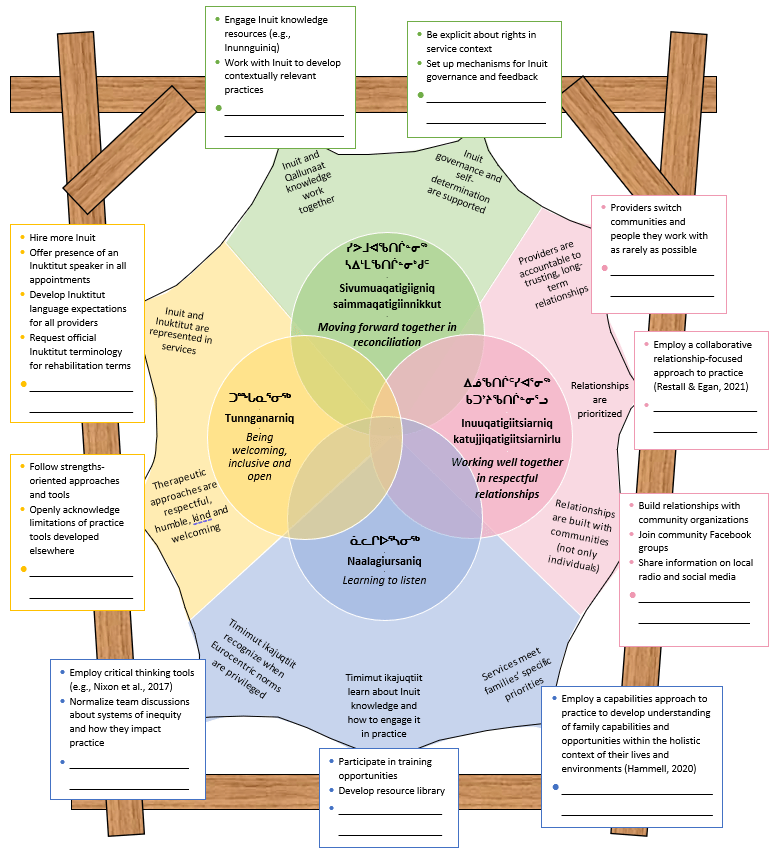

Guidance from Inuit knowledge concepts

Figure 1. Guidance from Inuit knowledge concepts that may offer direction for timimut ikajuqsivik for children and families in the Qikiqtani Region of Nunavut. An innirvik is a frame on which animal skins are stretched and dried to prepare them to be turned into clothing and useful goods. Likewise, this figure depicts a frame for preparing actions that can turn into useful practices. The interconnected circles at the centre of the figure contain Inuit knowledge concepts that can be thought of as guiding values for timimut ikajuqsivik for children. The text on the perimeter of the skin represents responsibilities that timimut ikajuqtiit can commit to as a way of enacting these values in practice. The text boxes on the innirvik frame contain examples of concrete and specific actions that could support the work of the responsibility statements.

Notes for timimut ikajuqsivik providers:

-

This figure is intended to be dynamic and evolving. The actions listed are just ideas. Blank spaces are included for you and the people you work with to fill in other actions that would bring these values to life.

-

The guiding concepts listed here are just a starting point. Keep your ears open for other concepts and approaches that may be helpful to your practice.

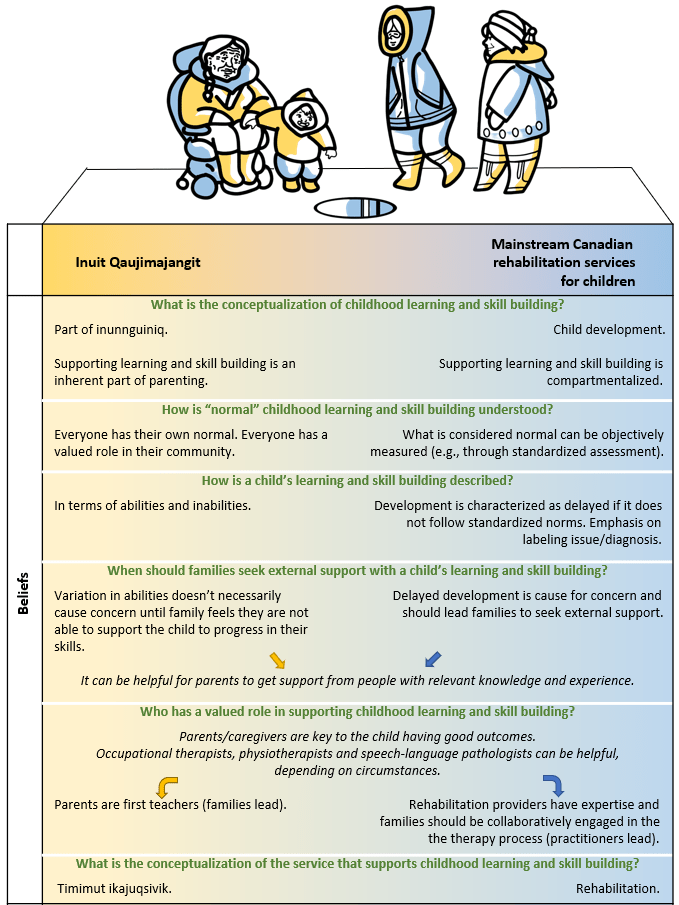

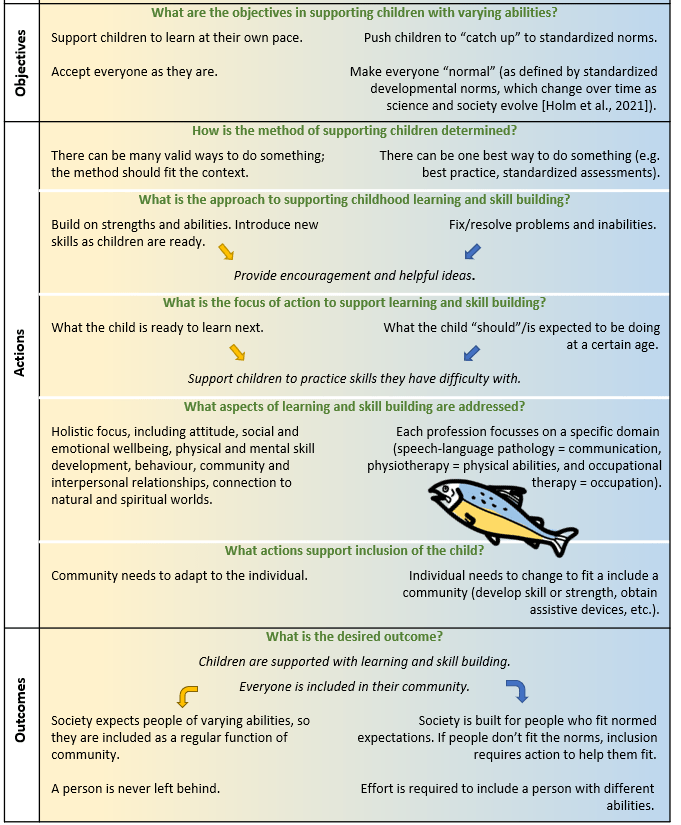

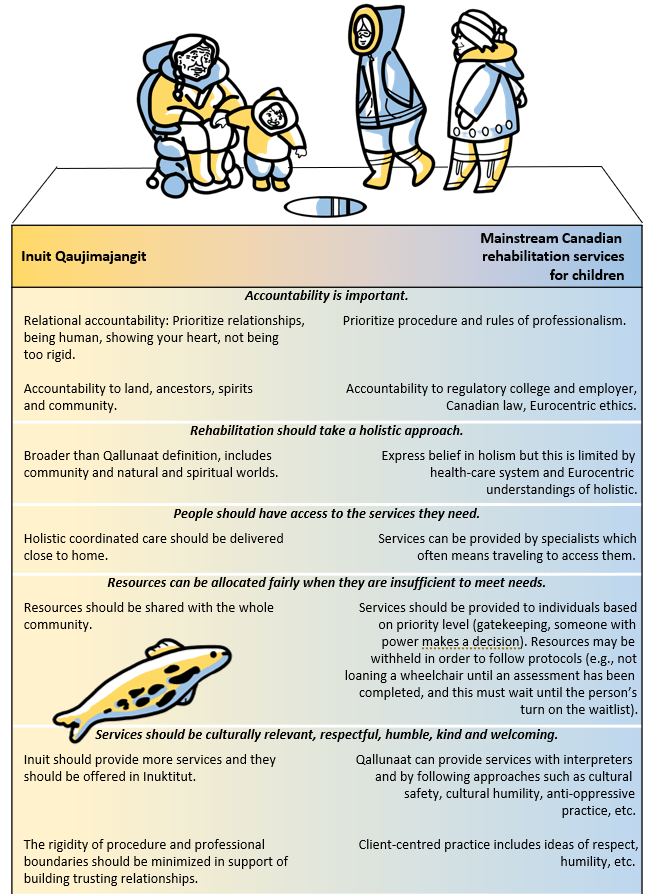

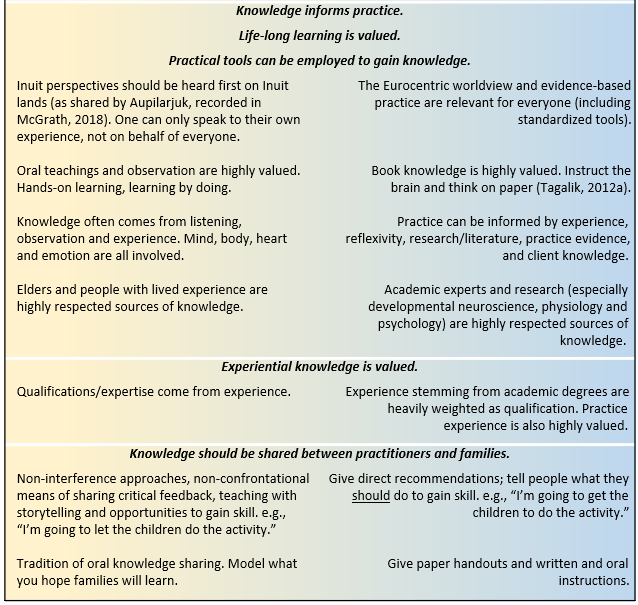

Examining Inuit Qaujimajangit alongside mainstream Canadian rehabilitation services

The following tables contrast Inuit Qaujimajangit (what Inuit know) with mainstream Canadian rehabilitation services for children. The tables are shaded from yellow to blue to show how the perspectives of these groups do not exist in an us/them dichotomy, but rather, on a spectrum. Participants expressed a range of perspectives that could be mapped across the width of the tables. Similarly, the evidence base and perspectives of timimut ikajuqsivik practitioners does not always strictly follow what is written in the right columns of these tables. (Consider especially the perspectives of Inuit timimut ikajuqsivik providers and non-Inuit providers who have practiced in Nunavut for many years.) The text on the left and right of these tables simply represents the greatest points of difference that emerged in the research. Centred text in the tables represents points of shared understanding across the two sets of perspectives. Illustrations by Aija Komangapik on the tables depict people coming together to fish, showing how people with differing perspectives can work together for the common good. Wherever on the spectrum of perspectives therapists or the people they work with might locate themselves, finding means to bridge difference while showing openness and respect is encouraged. Recognizing the power that Eurocentric/mainstream perspectives have, we can see the potential harm that can come from assuming they are universally relevant.

Table 1. How perspectival differences (from beliefs to objectives to actions to outcomes) influence support for childhood learning and skill building.

Table 2. Perspectival differences related to the structure and delivery of timimut ikajuqsivik/rehabilitation services.

Bridging ways of knowing

Figure 2. This figure uses the metaphor of picking a path to join friends at a fire to depict how Inuit knowledge and the knowledge of mainstream rehabilitation in Canada can differ. Itsutit (Arctic heather) has traditionally been used by Inuit for centuries as fuel for fire. Pallets and wood scraps that have been imported from southern Canada are now also commonly used for fire. Someone wishing to collect resources to build the fire following solely Inuit knowledge is likely to select a path on the left side of the image where they would find the most itsutit. Someone who only has knowledge from Southern Canada of how to build a fire is likely to select a path more to the right of the image where they could collect the most wood. There are also many path options that would allow someone to collect both itsutit and wood on their way to the fire. Each person headed to the fire, including Inuit and timimut ikajuqtiit/rehabilitation professionals (and those who identify as both), will have a unique path, collecting resources according to their understanding of what makes a good fire. If we imagine building a fire to be a shared goal of all people headed to the gathering, we can see that this goal can be achieved in different ways, fueled by differing kinds and proportions of resources. The paths of those headed to the fire may diverge and converge depending on alignments or tensions between their views about resources to build a fire. Note: Images of itsutit are depicted proportionally larger than they are in nature to be visible in the figure.

Summary of key messages from the research project as a whole:

-

Timimut ikajuqsivik for children can be informed by the wealth of Inuit knowledge on supporting childhood learning and skill building. E.g., see resources available at qhrc.ca

-

Eurocentric mainstream norms and systems of inequity (e.g., coloniality, the myth of meritocracy, Eurocentrism) raise barriers to Inuit knowledge being foregrounded in timimut ikajuqsivik practice. Therapists are encouraged to seek awareness and to resist these where possible.

-

There are wonderful opportunities for timimut ikajuqsivik to evolve towards increased contextual relevance and relational accountability in collaboration with Inuit stakeholders.

-

Opportunities exist within areas of difference between ways of knowing. Us/them dichotomies are unhelpful. Rather, we can focus on respecting one another’s positions and seeking ways to bridge them within relationships.